From A Casino Economy To A New Golden Age: Carlota Pérez At Drucker Forum 2017

Guest post by Steve Denning

When Carlota Pérez, the distinguished economic historian, finished speaking at the Drucker Forum 2017 , her talk elicited a sustained round of applause and there was already an avalanche of tributes on Twitter.

That’s because Pérez drew on decades of research, decoded economic problems that trouble us all and pointed to a clear path forward. Whereas most of us think that 20 or 30 years is a long-term perspective, Pérez takes a 240-year perspective. In so doing, she is able to show us patterns that are not visible when we only look at what has happened in our lifetimes.

Mark Twain allegedly said that history doesn’t repeat itself, but it does rhyme. In effect, Pérez’s brilliant work shows us what rhymes in the last 240 years of economic history.

Instead of history being just “one damn thing after another,” Pérez shows us that we are actually living through repeating longer-term cycles. In this way, the options—and consequences of different decisions—become much clearer. Here’s her talk:

Carlota Pérez: What I am going to argue today is that it’s time for government to come back boldly, wisely, and adequately. In saying this, I know that I’m swimming against the tide. But I also know that what I am saying is solidly grounded in the history of technological revolutions and the associated role of finance.

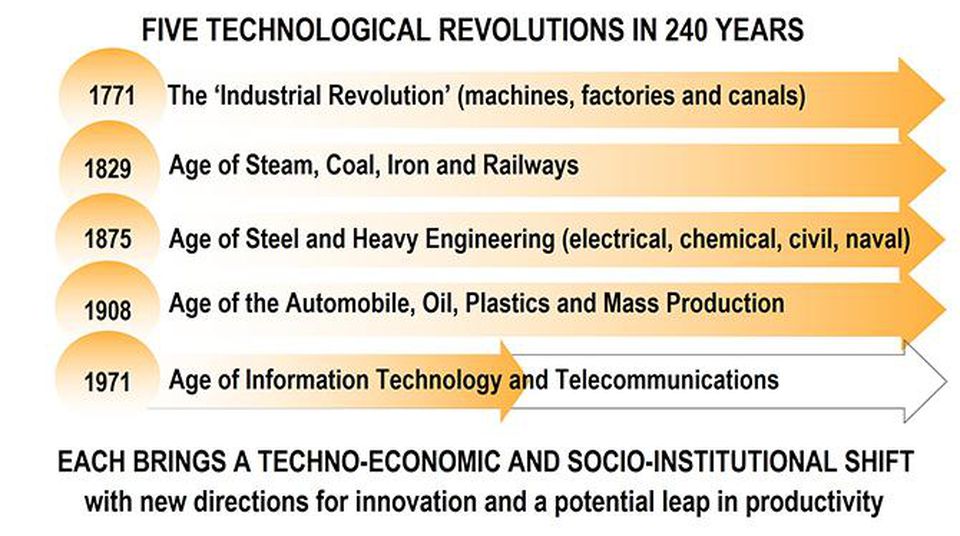

Five Technological Revolutions

To simplify and summarize: there have been five technological revolutions over the last 240 years (in this, I follow Schumpeter’s lead, rather than some recent interpretations, which count two, three or four.)

Carlota Pérez: five technological revolutions

The first was the Industrial Revolution, beginning in the 1770s, with machines, factories, and canals, which were the Internet of that time.

The second was the age of steam, coal, iron and railways, beginning around 1830. Both of these technological revolutions evolved mainly in the UK.

After that, beginning around 1875, we had the first globalisation. It was an age of steel and heavy engineering, with transcontinental railways, rapid steamships and transoceanic telegraph, allowing counter-seasonal trade of wheat and meat. It was the time when the U.S. and Germany forged ahead, as China and India are doing today. It became possible to go in steamships very quickly to the southern hemisphere and bring back products like meat, wheat, and minerals. It was a time when Australia, New Zealand and South Africa could make a living in the global economy. It was an interesting time and in some ways similar to ours.

After that, from the 1910s, the U.S. began its rise to global leadership when Henry Ford’s Model-T initiated the age of the automobile, mass production, cheap oil and plastics. This was the era that created the basis for our current one as well as our current environmental problems.

Beginning in the 1970s, we entered the fifth and current technological revolution. It is the age of computers, information technology and telecommunications. We are right in the middle of this revolution. What I will argue is that we are only half way along in the diffusion path of this revolution.

Each of these five revolutions has brought new life-styles, new directions for innovation, and a huge potential leap in productivity for the whole economy. They not only brought changes in some areas; they are major technical, social, and institutional shifts. That’s why we call them revolutions, otherwise they wouldn’t deserve the name.

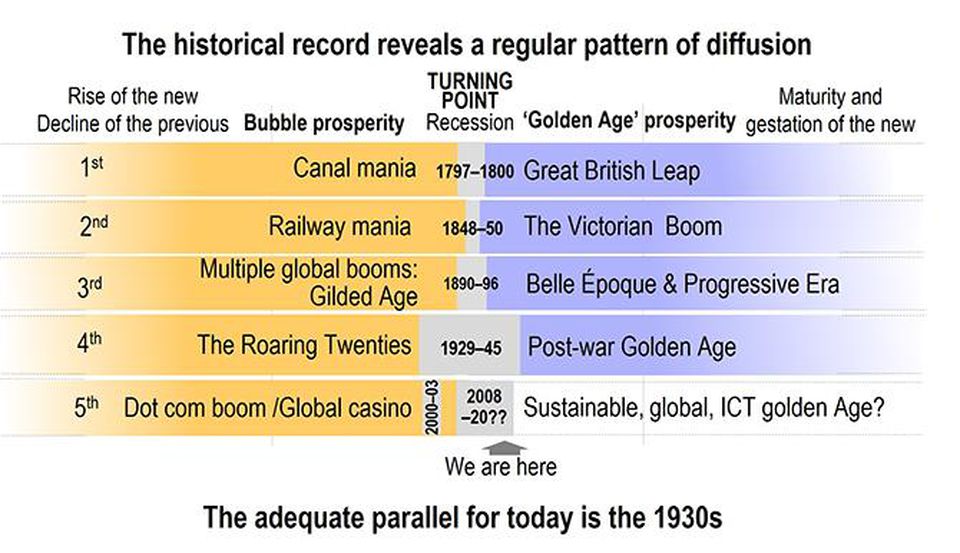

The Pattern Of Change In A Technological Revolution

What’s interesting for us today is that the historical record reveals a regular pattern in the diffusion process. It takes place in two halves. First, we have the rise of the new technology that occurs during the decline of the previous revolution. It’s like the 1980s, when we had inflation with the old technologies, which were yielding decreasing returns, while the information technology companies were growing fast with steadily increasing returns (and decreasing prices).

Carlota Pérez: the pattern of diffusion

That first half is the installation period of the new technology, which leads to and ends with one or more bubble prosperities –as in the late 1990s and mid-2000s– when the financial sector and the casino economy take over.

Then the bubble or bubbles burst and we have a recession, as we have now, that might last anywhere from 2 years to 13 years or more.

That recession phase is what I call the ‘turning point’, because it is the time when the control of investment shifts from finance to production, normally with the aid of the State. When that has happened in the past, we have experienced strong growth in what can be called a Golden Age, with broad-based prosperity.

But the Golden Age cannot continue forever. Returns from the new technology start to decline. Then comes the inevitable maturity of that technological revolution and the process starts all over again with the next one.

“To make this happen, we need new mindsets. Whenever these technological revolutions have occurred in the past, the initial response has always been to try to shoehorn the new technology into old lifestyles and ways of thinking.”

The Sequence Of Changes: The Role Of The Turning Point

Let’s see how this has happened in history. In the first—the ‘Industrial revolution’—we had the Canal Mania and then the Canal Panic during the Napoleonic Wars, leading to the great British leap forward.

Then we had the Railway Mania and the subsequent Railway Panic, when it became apparent, as in each case, that there had been over-investment. After a short recession, came the Victorian boom times of the 1850s and 1860s in the UK, with capitalist Britain increasingly assuming global leadership .

Then the Age of Steel, from the 1870s onwards, led to multiple global booms—in the U.S. Germany, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and Argentina—as massive global opportunities led to an investment boom. Everyone wanted to participate. That is, until a series of crashes came in various forms across the world.

Chastened by the crashes, the financial sector in the United States and Germany returned its focus for a while to funding the real economy, which stabilised the situation for a period. The result was less happy for Argentina which ceased to be a major player in the world economy. Great Britain concentrated on globalisation and empire rather than investing enough in electricity, steel and the new chemicals. So, it began losing its leadership position in the global economy. Once again, the change involved a great deal of waste and pain, but the financial sector had funded the infrastructure for the new global economy.

From the late 1890s, came a period of relative calm and prosperity with the Belle Époque in Europe and the Progressive Era in the U.S. in which some monopolies were broken up and issues of income inequality were addressed.

The fourth revolution–Mass Production—led to massive investment and growth in the Roaring Twenties until the Crash of 1929, which in turn led to the Depression of the 1930s. You could look at this period as a long turning point of some 13 years, which paved the way for a period of broad-based prosperity, including the Second World War, which taught business the advantages of working with government.

Then from 1970 onwards, we have had the age of Computers and Telecommunications The mid-1990s, when government handed over the Internet to business, saw rapid economic growth, ending in the Dot.com crash in 2000 and then the casino economy of the mid-2000s, with the collapse across the world of various bubbles in housing and synthetic financial instruments.

The Current Turning Point

Now in 2017, we are in the middle of another turning point, as in the 1930s, and we could have a period of sustained global prosperity if appropriate action is taken.

Now, as in the 1930s, we have structural unemployment, low investment, growing inequality, a sense of hopelessness, risk-averse finance with trillions of dollars sitting on the sidelines, feeble growth, social unrest, recessions, and talk of secular economic stagnation. Populist leaders find massive following precisely because of these issues. They exploit the rampant xenophobia against various sub-groups. It could be the Jews or the Muslims. Somebody must be at fault. And large-scale economic migrations further aggravate the xenophobia.

Despite these problems, there was then, and is now, a huge underlying technological potential (as a result of the ongoing technological revolution), but the potential cannot be realized without a clear common synergistic direction.

That is why now is the right historical moment for the government to come back on the scene, boldly, actively and wisely. In a turning point, government is not the problem: government is the solution.

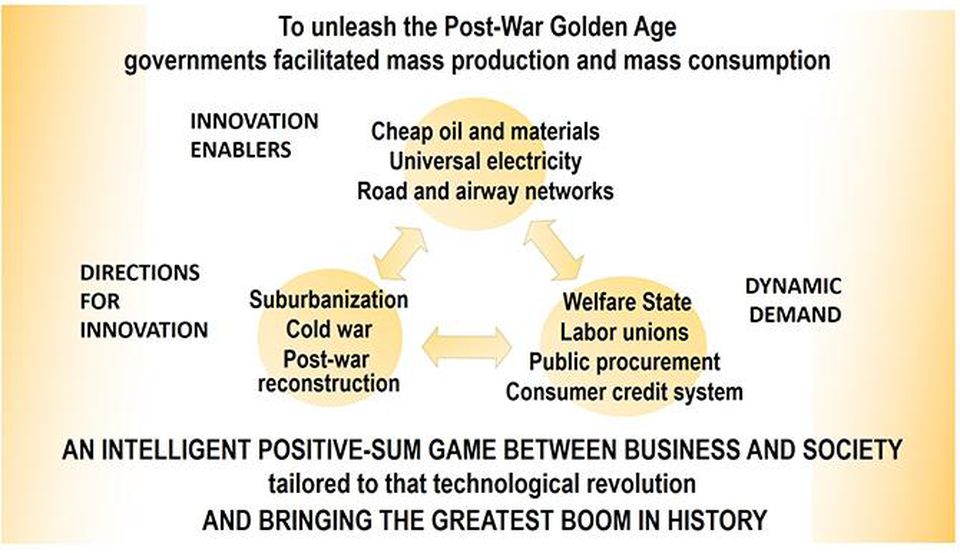

This is what eventually happened from the 1940s. Government action and the Second World War led to mass production and mass consumption. Large numbers of people had access to relatively cheap products. Suburbanisation made it profitable for firms to innovate for the family in the electric home with its insatiable hunger for new products. At the same time, the Cold War led to government investment in high tech. The reconstruction of Europe also stimulated economic growth and the demand for equipment and other goods.

Carlota Pérez: post-war golden age

The welfare state enabled mass consumption. That’s one reason why high taxes were possible without resistance. The top rate was around 90% throughout the 50s. The money went out of tax-payers’ pockets, passed through the hands of government, and came back as solvent demand for consumer goods or procurement. Firms prospered because they were able to pursue an agreed common vision of what “the good society” looked like and what innovation was needed to make it happen. Everyone was going to have a home with cheap appliances. Credit was available that enabled people to buy houses and goods. It was an intelligent positive-sum game between government, business and society that led to the greatest economic boom in history.

A New Positive-Sum Game: Green Growth?

Moving on to our own time, we can see that there are new possibilities for an intelligent positive-sum game. The ongoing technological revolution based on computers and telecommunications has immense potential benefits for everyone. Yet there are also risks. We are facing environmental issues: not just global warming and pollution but also a scarcity of natural resources. We cannot give every Chinese and Indian person the American Way of Life: we simply don’t have seven planets.

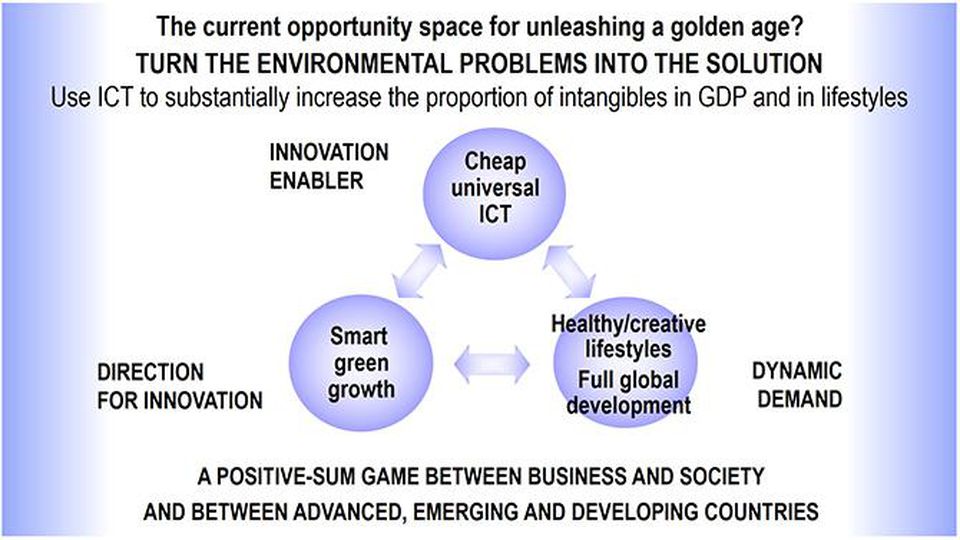

Carlota Pérez: environment as a solution

What to do? We need to turn our environmental problems into economic solutions. We need to use information technology to increase the proportion of intangible services available world-wide. We need Internet access everywhere, both universal and cheap. The direction for innovation is clear: smart, green growth. This of course will mean changes in life-style, just as we have seen changes in life-styles in all previous technological revolutions. The technology generates the new possibilities and the new needs provide dynamic demand. The adoption of the new life-styles leads to the jobs that replace the ones eliminated by the ongoing technological revolution and the new jobs enable widespread prosperity.

The other dimension of increasing demand today is the economic growth needed, not just in China and India, but in all of Asia and Africa and Latin America. Full global development would both improve the lives of the majorities and provide demand for capital goods, engineering and all the things that the developed world can provide.

The Need For New Mindsets

So, what would we get if government acted boldly? We would get a positive-sum game for business and society as before, but now also between advanced, emerging and developing countries.

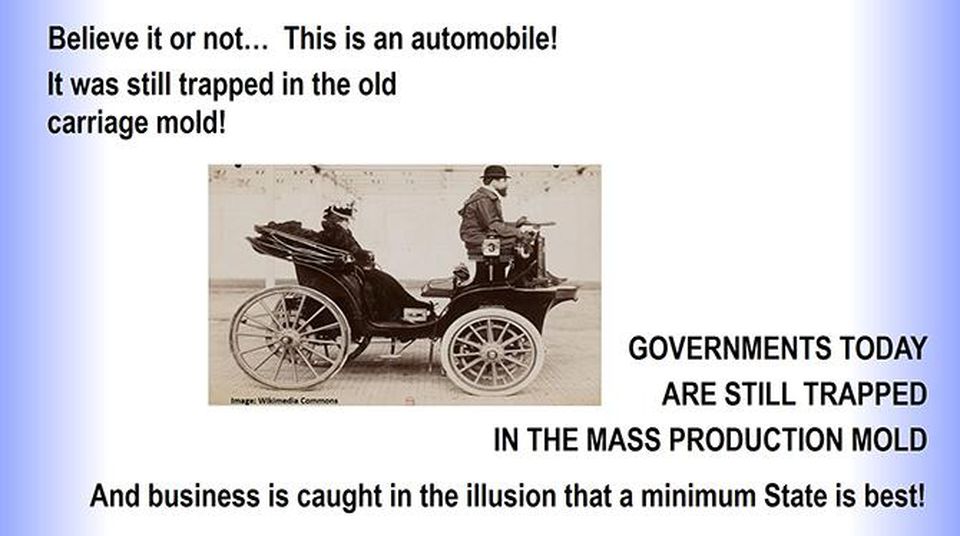

To make this happen, we need new mindsets. Whenever these technological revolutions have occurred in the past, the initial response has always been to try to shoehorn the new technology into old lifestyles and ways of thinking. The result is a failure to capture the full benefit of the new technology. We see people, firms and governments clumsily trying to do things in the old way with the new technology.

For example, when the automobile was first invented, the first examples were like motorised versions of a horse and cart. It took time for people to grasp the possibilities of the new technology, independently of what had gone before.

At first, new technology mimics the old: the automobile – Carlota Perez; Wikimedia

We face similar issues today. Governments are still trapped in a mass-production mindset, while business is trapped in the illusion that a minimum state is best. If we are going to achieve economic growth with greater income equality and sustainable well-being, as the participants of the Drucker Forum clearly want, we need to get out of both traps and start working together.

Thank you!

Carlota Pérez will be speaking at AgileAus20 on 15-16 June 2020 in Melbourne – you can find out more at agileaustralia.com.au/2020/

This article was written by Steve Denning and is reproduced with permission from Forbes. Copyright remains with Stephen Denning, all rights reserved.

Stay in the loop

To receive updates about AgileAus and be subscribed to the mailing list, send us an email with your first name, last name and email address to signup@agileaustralia.com.au.

0 Comments