How applying behavioural economics can (and should) increase your product outcomes tenfold

My lightbulb experiment in 2017

As Jeff Patton noted, ‘focusing on product outcomes will shift you to a product mindset’.

I’ve become convinced through years of applied experience that behavioural economics can (and should) produce 10x the outcomes and create scalable learning to the rest of your products.

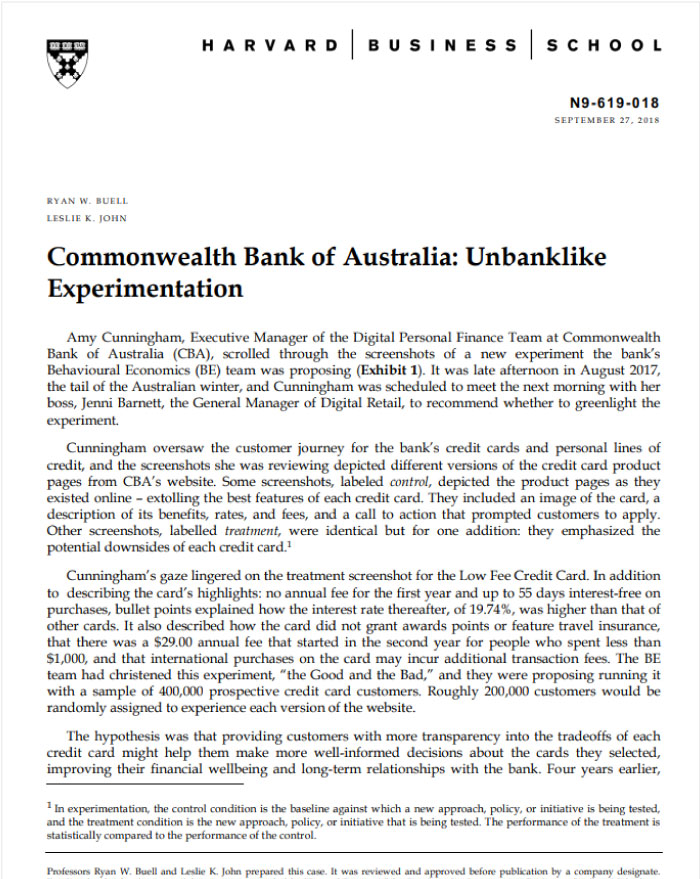

I was fortunate to work with some leading academics including Harvard and CBA’s Behavioural Economics Team tasked with applying the latest research to help customers make better decisions.

Up until then I’d held individual and leadership roles, accountable for – amongst other things – digital sales, service, retention, customer experience and digitisation. This involved digital delivery and running experiments across platforms. The experiments were the ‘vanilla’ kind where intuition based ideation would add a ‘call to action’, visual designs change or reminder messages for customers. Only later, did I realise many of the missed opportunities.

2017 gave me a lightbulb moment which changed the trajectory of my career.

It convinced me that applying behavioural economics could (and should) increase measurable outcomes tenfold and produce deep, scalable learning. It also led me to complete a Masters in Behavioural Economics at the University of Technology, Sydney.

The short version of the long story is this.

For many years, Professor Ryan Buell from Harvard along with his colleagues had conducted deep research into the customer and business benefits of transparency.

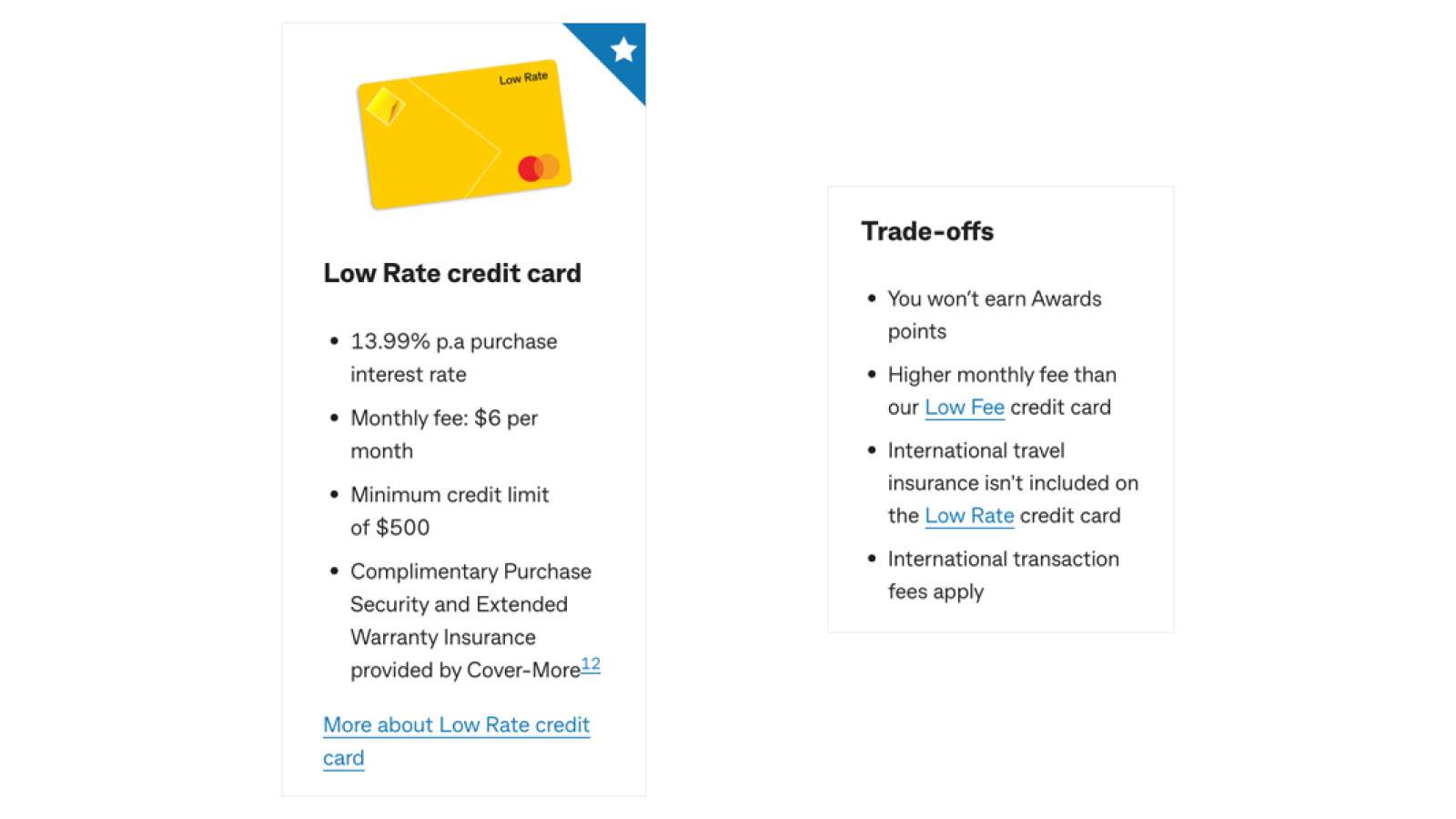

In partnership, I helped lead a scaled experiment to 400,000 prospective customers that highlighted downsides between different credit cards, rather than just the traditionally emphasised features and benefits.

This could be considered counter-intuitive and opposed to conventional wisdom which suggests to emphasise product benefits.

The result?

As the Australian Financial Review put it:

“CBA customers given more transparency about their credit cards exhibited higher-quality service relationships over time and had monthly spending 9.9 per cent higher.

Their cancellation rates were 20.5 per cent lower than those who were not told about trade-offs between different products.”

The experiment insights were profound, for many reasons including:

- Measure deeply & experiment, otherwise you’ll miss profound impacts

- Doing things that are having impacts which you are not aware of

- Good intentions & intuitions are wrong half the time (you just don’t know which half)

- If you have a clear theory it will increase your chance of success

- It is possible to drive customer & business outcomes together

This experiment was subsequently published as a Harvard Case study and opened my eyes to the power of applied behavioural economics.

Naturally this raises the question…

What is behavioural economics (and why is it so important)?

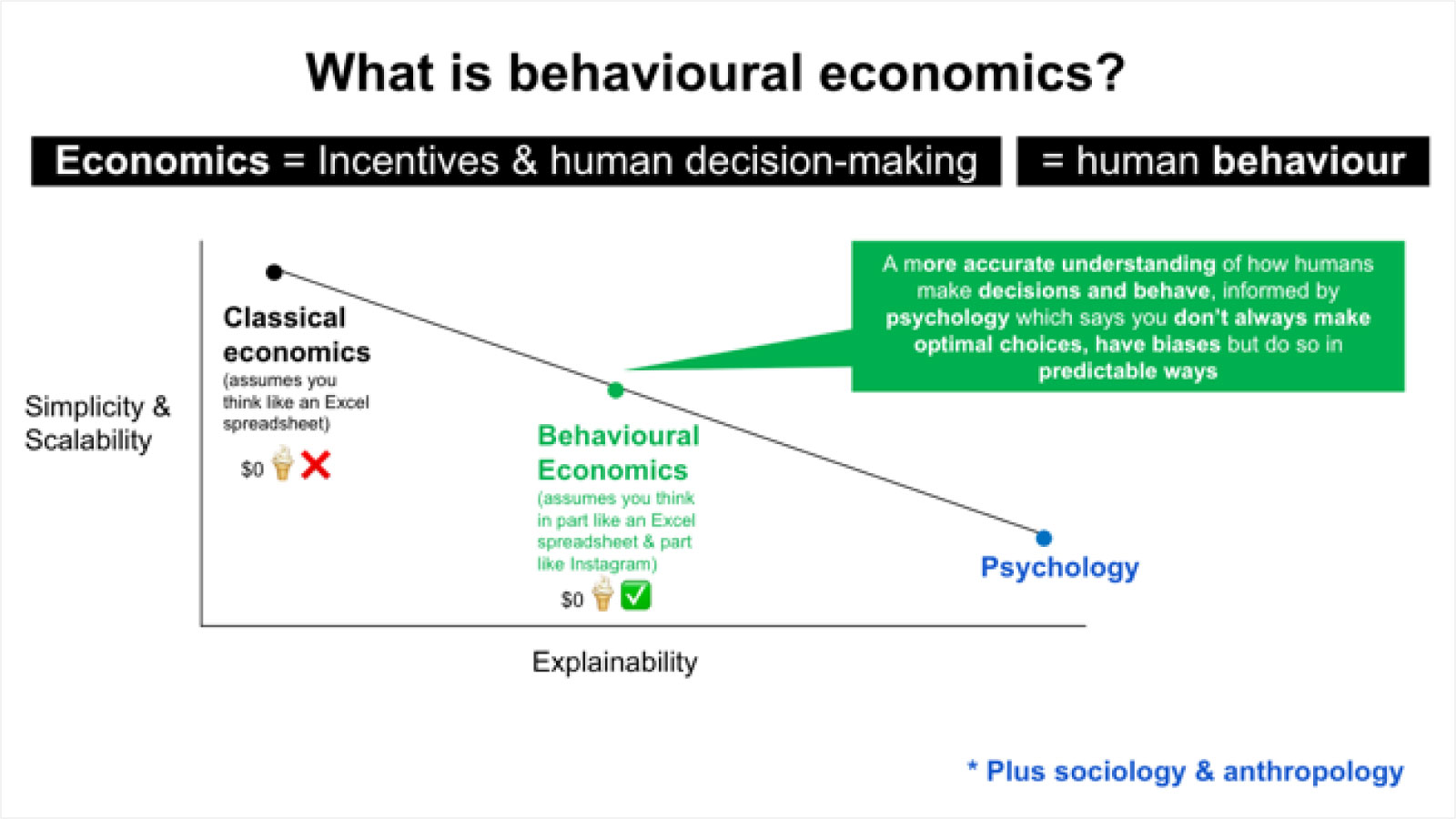

What is behavioural economics? Here is a simple explanation.

Economics is the study of how people decide (and behave) when there is uncertainty and scarcity.

Classical economics assumes people are kind of like an Excel spreadsheet:

- Rational and self-interested

- Aim to maximise satisfaction

- Have perfect information

- Make each decision independently

- Preferences are consistent and predictable over time

But in the 1970s, psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky showed through various studies and experiments that people often rely on biases and heuristics (mental shortcuts) in making decisions which weren’t accounted for in classical economic predictions.

In other words, people are kind of like an Excel spreadsheet, and kind of like the Instagram app.

So, the behavioural economics revolution began.

But what does this look like in actual, real life?

In real life…

Consider this.

With an average person spending $5 per day for coffee, why might a free scoop of ice cream (equivalent in price) cause queues?

For example, here is a scene I captured when a free scoop of gelato was being given away.

In 2013 to celebrate Dubai’s announcement as the host of Expo 2020, Baskin Robbins announced free ice cream between 1-3pm, causing an “ice cream mob” across the city

Rationalistically, it doesn’t make sense.

Ice cream was freely available for a modest price (a similar price to a daily coffee which 50% of people freely spend) but dropping the price to $0 had a disproportionately large effect.

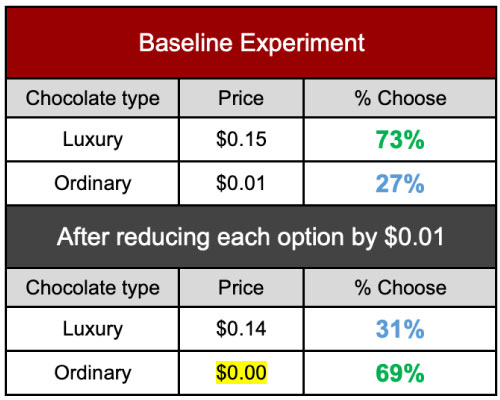

This effect was observed in a lab experiment, participants were given the choice:

- Luxury chocolate for $0.15

- Ordinary chocolate for $0.01

The portion who chose luxury chocolate? 73%

However, when each price was lowered by a measly $0.01, the options became:

- Luxury chocolate for $0.14

- Ordinary chocolate for $0.00

The portion who now chose luxury chocolate? 31%

The preferences almost entirely reversed…over a single cent!

Here is a table which shows the contrast.

How does this apply to product?

How can (and should) behavioural economics 10x your product?

In a product-led approach, what is a product?

A product is an offering that solves a specific need for customers while solving business and technology problems.

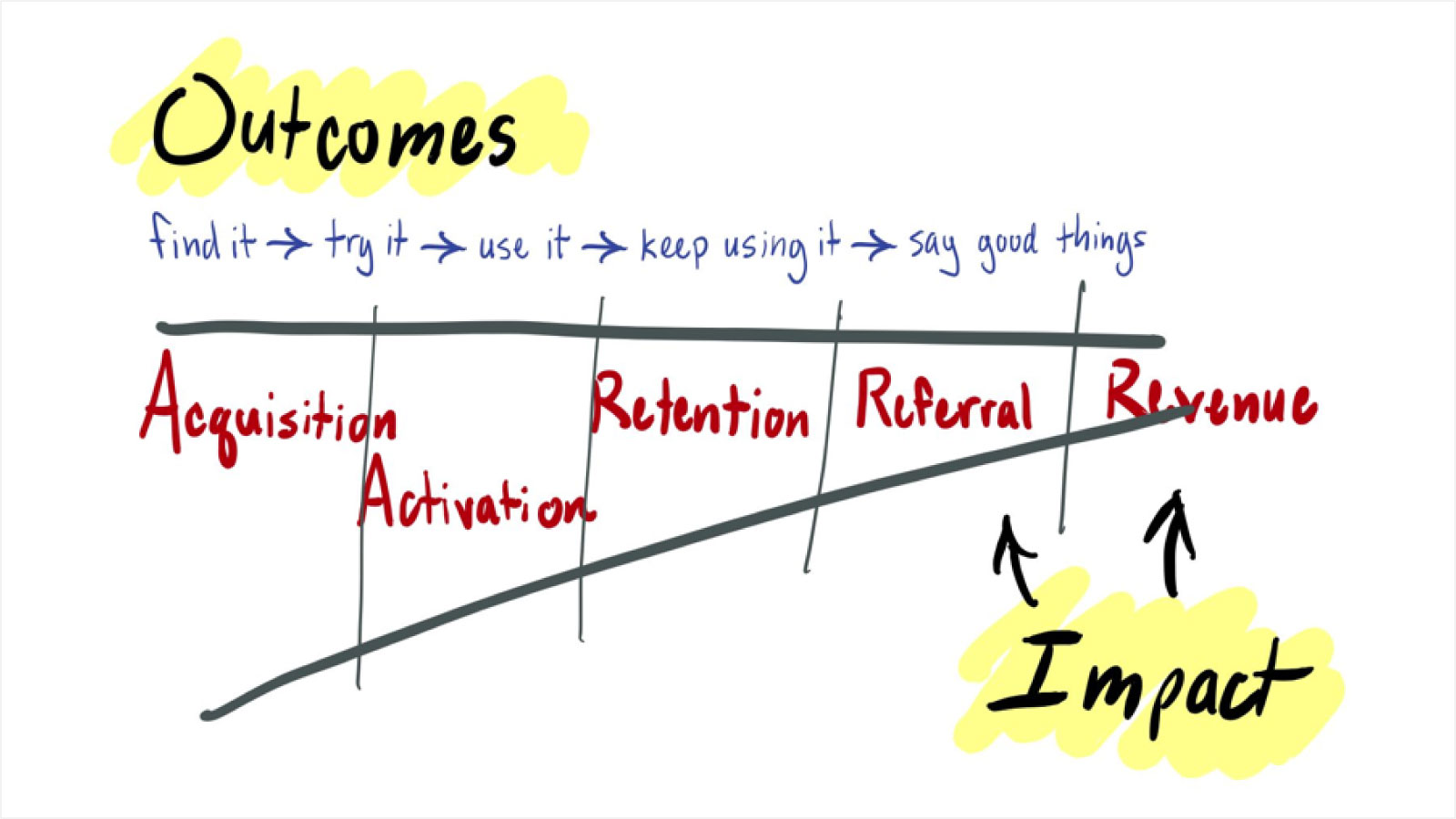

For the purpose of simplicity, this simple Jeff Patton diagram shows the connection between customer outcomes and business impact for a product.

So, product is seeking to help customers:

- Find the product

- Try the product

- Use it

- Keep using it

- Saying good things about it

By having a more accurate understanding of how people actually make decisions and therefore behave will help drive those customer behaviours.

This is where the product, outcomes, experimentation and behavioural economics converge to make magic.

Stay tuned for the next blogpost in this series to explore how to apply behavioural economics (and know if it worked)…

NEXT POST

A practical way to apply behavioural economics now (and how to know if it worked)…

Stay in the loop

To receive updates about AgileAus and be subscribed to the mailing list, send us an email with your first name, last name and email address to signup@agileaustralia.com.au.

0 Comments