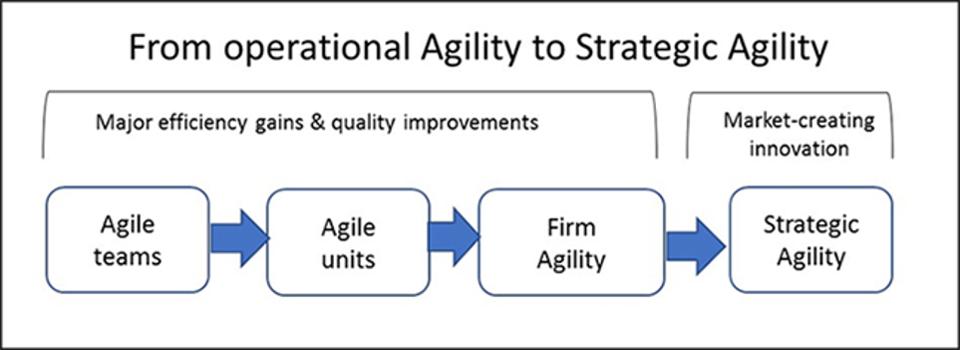

From operational agility to strategic agility

Find out more about Steve Denning’s full day workshops in March and June, his keynote role at AgileAus18, and his participation in The Deep Dive 2018.

This is the first in a series of blogs drawn from Steve Denning’s Forbes.com articles and his forthcoming book, The Age of Agile (Amacom: February 2018).

As Agile mindsets and processes increasingly enter the management mainstream, firms are learning how to draw on the full talents of those doing the work, involve customers at every stage of product development and so generate innovations that customers value.

Most organisations implementing Agile are still preoccupied with upgrading existing products and services through cost reductions, time savings or quality enhancements for existing customers (i.e. what one might call operational agility). What they — and the wider management community — need to realise is that the main financial benefits from Agile management will flow from the next frontier: generating innovations that create entirely new markets by turning non-customers into customers, i.e. Strategic Agility. (This is the dark secret of the Agile movement.)

Chart by Steve Denning

To use a metaphor, operational agility succeeds in delivering a steady flow of additional value for customers, akin to filling a series of small cups with water. By contrast, Strategic Agility is akin to filling a whole bucket. The shift from cups to buckets is a difference in the scale of the financial impact.

Make no mistake: operational agility is still a good thing. In fact, it’s increasingly necessary for a firm to survive. And it’s also the foundation for Strategic Agility. But it is not enough. In a marketplace where competitors are often quick to match improvements to existing products and services and where power in the marketplace has decisively shifted to customers, it can be difficult for firms to monetise those improvements. Amid intense competition, customers with choices and access to reliable information are frequently able to demand that quality improvements be forthcoming at no cost, or even lower cost. In addition, firms need to master Strategic Agility.

This article explores what’s involved in systematically achieving Strategic Agility. Strategic Agility occurs in two main ways: either as a by-product of operational agility or through use of an explicit playbook to generate market-creating innovation.

A: By-product Of Operational Agility

At Spotify, for instance, Discover Weekly was intended to solve a known problem with an existing product: the difficulty that existing users were having in locating music they would truly love, in Spotify’s vast library of millions of songs. Users were spending most of their time searching for songs, rather than actually listening to music that they loved. Discover Weekly solved that problem for existing users, by matching users’ tastes with billions of existing playlists and presenting a fresh personalised playlist to each user each week. But it went further: the innovation was so wildly successful that it brought in tens of millions of new users and became in effect a brand in itself, in some countries perhaps even better known than “Spotify”.

Spotify’s approach to innovation is mainly based on the lean-startup principle that views the biggest risk in innovation to be building the wrong thing. In essence, you start by imagining what you have in mind. Then you check whether any customer would want it. Then you build a prototype. Then you go on tweaking it, adding features that may help with monetisation.

While this approach can work well in terms of improving existing products for existingusers, it has several limitations in terms of systematically generating market-creating innovations.

First, in an ongoing organisation as opposed to a startup, Agile teams are mainly focused on making things better for existing users. If the improvement creates new markets of users and non-users, that is a happy accident, rather than the main goal. To get more consistent success in generating market-creating innovations, an explicit focus on attracting non-users is needed.

Second, market-creating innovations sometimes involve eliminating features, not adding or improving them. Paradoxically, less may be more. Thus, a firm may generate market-creating innovation by eliminating elements that it or other firms are marketing as high-value for customers. The resulting simplification can sometimes perform the dual function of lowering costs and drawing in vast numbers of new users. A classic case is Southwest Airlines which based its business on eliminating the very features which the rest of the airline industry trumpet: meals, lounges and seating choices.

Yet the decision to eliminate seemingly popular features is not one that is easily taken at the level of the Agile team. Agile teams are generally focused on adding new features requested by existing customers. Teams are unlikely to propose or carry out experiments to eliminate key services that would bring in new customers, since it is usually assumed that features being used by existing customers must be valuable to them. Moreover, existing features typically have their own constituencies within the organisation: a team that has created a feature often becomes a lobby for retaining and improving it. Unless there is an explicit decision at a higher level to pursue the elimination of features with the goal of attracting new non-customers, it is unlikely to happen.

Third, market-creating innovations can lead to self-cannibalisation of the firm’s existing products and so generate a reluctance to interfere with a current revenue stream. Thus, it wasn’t an easy decision within Apple to include a music-playing capability in the iPhone, because it cannibalised the market for the iPod. Initially, even Steve Jobs himself is said to have opposed it. It was only the realisation that if Apple didn’t disrupt itself, some other competitor would do so that led to the eventual decision to include music playing in the iPhone. Thus, eventually a decision was made to sacrifice the revenue stream from the iPod in favour of the larger potential gains from the iPhone. Such a decision is never easy and typically it has to be taken at the highest levels of the organisation.

Fourth, work on improving existing features can be suitable for low-investment market-creation, as at Uber and Airbnb. But it’s rarely a solution for innovation that requires substantial technical innovation or financial investment. When the firm is imbued with lean-startup thinking, the firm often ends up pursuing a series of “small bets”, to the neglect of “big bets.”

Fifth, if corporate incentives flow to people who can “move the needle” by showing immediate results from improving an existing product for existing customers, then any slow-moving “big bets” under consideration will tend to morph into “small bets” that generate quick wins. The pressure to “get results now” will make it harder to attract top talent to work on expensive slow-gestating investments that could have huge gains if they were to be pursued. And those who are working on developing something completely new may become discouraged as they will have no immediate results to show for their efforts. To overcome these pressures, top management must delineate the importance of winning “big bets,” even if their gestation is slow, and create specific incentives to accomplish them.

Finally, lean-startup thinking is not well-suited to deal with decisions on market-creating innovations involving large investments in a new product, when no one knows in advance whether the idea will work or not. Often, it isn’t possible initially to put a prototype in front of potential users and see whether they will use it and be thrilled by it. In most cases, there will be no “hard data” on which to base a decision.

In the absence of an explicit playbook to foster market-creating innovation, decisions on such large investments will tend to be based on corporate politics: the loudest voice having the most hierarchical clout will end up making the call. In the absence of hard numbers, proceeding with the investment will often be perceived as presenting too great a risk and the investment will be abandoned. If a decision is finally made to go ahead with investing in a capital-intensive innovation after a bruising battle at the top, it can be hard for the organisation to change course even if actual data starts to show that the firm is on the wrong track. In such situations, the firm may continue to invest in a losing proposition, until it turns into a disaster that is too obvious to ignore.

Yet it doesn’t have to be this way if there is a playbook for generating market-creating innovations. There are well-established principles that can lead to sustained success with market-creating innovations. They involve understanding the art and science of Strategic Agility.

B: A Playbook For Market-Creating Value Propositions

A playbook for Strategic Agility provides the basis for generating market-creating value propositions that systematically create new markets for products or services that will enjoy strong demand and growth from both customers and non-customers. The aim is to create products or services that enjoy little competition, precisely because they meet a need in the marketplace that is currently not being met — the so-called “blue oceans” of profitability.

Market-creating value propositions involve a shift in thinking from the known to the unknown — from existing products to unknown products, and from users to non-users of the firm’s products. This in turn means redefining how needs are being met and in the process, discovering value for customers and non-customers from elements that lie outside current thinking, within both the firm and the industry.

It also means a shift from thinking of outputs of the organisation to considering outcomes for the customer or end user. “Instead of thinking of your company as providing a particular type of product or service — electric power, health records management, or automobile components,” writes consultant Norbert Schwieters, “think of it as a producer of outcomes. The customer needs to get somewhere, so you’re not a car company; you’re a facilitator of that outcome. The house is cold, so you help make it warm, possibly without supplying the necessary fuel… Customers, in turn, are making fewer purchases to accumulate physical things and more purchases to achieve outcomes, convenience, and value.”

Thus Christensen and colleagues argue in their book, Competing Against Luck, against “defining customer needs through typical market research and then delivering against them.” This can lead to a focus on “functional needs without taking into account the broader social and emotional dimensions of a customer’s struggle… And in many cases emotional and social could be on the same plane as functional needs — and maybe even be a driver.” For example, the Rolex watch is a status symbol, and most of its value is based on the intangible deliverables.

©Stephen Denning 2017: The content of these articles was first published in Forbes.com and is reproduced here with permission from Stephen Denning. All rights reserved. Some of the material in this article will appear in a different form in the forthcoming book, The Age of Agile (Amacom: February 2018).

Check back on the AgileAus blog for the next installment of this strategic agility series with Steve Denning! For the full article, visit Forbes.com.

Stay in the loop

To receive updates about AgileAus and be subscribed to the mailing list, send us an email with your first name, last name and email address to signup@agileaustralia.com.au.

0 Comments